"It is all one long day"

You know the feeling. Like when you're into a band. Before they get big, before pop culture and the zeitgeist catch on to them. When it feels like they're just yours, and you know that that time can't last and as such, its even more precious. Or even sometimes you don't see it coming, you can't imagine the mainstream will ever want them, they're too good for the mainstream. But the mainstream, the zeitgeist...its a hungry beast, and its belly can never be filled. It comes for all the good stuff, eventually. That song, the one only you seemed to know, the one you love - it shows up in a trailer for some romantic comedy. It gets covered by somebody crap. An album is reissued. Reissued with previously unreleased songs, b-sides, some demos you didn't have before. Reviewed and raved over in all the papers, the music magazines. Here comes the zeitgeist, its big mouth open.

I hate that. I've had bands, of course. Back when I was younger and into slightly fashionable music, I suppose. I saw The Strokes on their first UK tour, in Dublin, when they had only released one single. But they already had a massive buzz around them and every hipster in the city was at that gig. A few months later, the album came out and they were huge. Mercury Rev prior to Deserters Songs. Wilco before Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. Elliott Smith. None of those acts are exactly U2, I know, but they all became a lot more successful at a certain point long after I had gotten to them, and its relative. I knew guys in school who were massive Nirvana fans from Bleach onwards, way before Nevermind came out. Imagine how they felt when that band, "their" band, the band that at one point almost nobody they talked to would have heard of, when that band became the biggest band in the world? I know it used to annoy me, stimulating some elitist nerve I carry around inside. It never feels the same afterwards, when the world has discovered something you love in an intensely private and personal way. The internet has changed so many things about the way we think about and consume music, and this is one of them. Nothing is obscure anymore. If you're interested in a band, they're out there, just a few keytaps away. Elitism is irrelevant. The internet doesn't care.

Instead, nowadays it happens to me mainly with writers. I'll give you an example: Richard Yates. I first heard of Richard Yates on the dedication to Richard Ford's collection of novellas, "Women With Men" in 1997. Ford, one of my favourite writers, thanks Yates. If it was good enough for Ford, it was good enough for me, and so I set off in search of Yates. Back then I didn't have a computer, I hadn't really used the net much, and so Amazon wasn't an option. So I had to go to regular bookshops in a fruitless quest. No Yates anywhere. I asked in Waterstones and there were no Yates books in print in Britain or Ireland. There was one available on import from America, but it would take around a month to arrive. I ordered it and a week or so later found a copy of Yates' "Young Hearts Crying" in a Dublin secondhand bookshop. That, perhaps Yates' worst novel, was the first thing I ever read by him. And it blew me away. I call it his worst novel, but it is only by comparison to the high standard of the rest of his work that it seems lesser. The simplicity of the writing, his fine storytelling, his observational skills and understanding of people, the sense of pessimism and loss in every page seemed incredibly fresh and vital to me. I had a new writer to love and read, always an exciting moment for a reader.

The book I had ordered from Waterstones turned out to be "Revolutionary Road", probably Yates' best and most famous work. Its also one of the bleakest novels I've ever read, but don't let that put you off. It was nominated for the National Book Award in 1962 alongside Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" and Walker Percy's amazing "The Moviegoer", in what constitutes an incredibly strong field of lasting quality. It follows the decline of the marriage of Frank and April Wheeler in the sterile suburbia of 1950s America with an acuity of vision not many writers can match. It is beautifully written in Yates' plain, understated prose, but the characterisation and deftly drawn relationships make it as gripping as any thriller. The bleakness of Yates' sensibility was obvious from reading just two of his books, but seemed essential to the quality of his work, somehow. He saw how the world was, and he recorded it precisely. I loved it, of course. It seemed impossible that a writer as brilliant as Yates evidently was could be so little-known. Why was he not acknowledged as one of the greats of 20th Century American literature? How had such an artist slipped through the net? Well, the net was slowly closing around Yates, though I didn't know it yet.

Back then, I was temporarily stymied in my quest for more Yates by the unavailability of anymore Yates. Once I gained Internet access I dicovered that some of his other books, though long out-of-print, were available secondhand online. I bought The Good School this way. I also found an article about him, written by Stewart O'Nan, another more-neglected-than-he-deserves American novelist, which was a good combination of brief biography and literary criticism. It descibed Yates as a "writers' writer". I liked that. Then his work started to dribble out in new editions. "Revolutionary Road" was first, with an introduction by Ford. It received brilliant reviews in the UK press. I felt the sting of that. Then a Collected volume of his Complete Short Stories. Which I bought, glad it was available to me but a little resentful, too. Over the last 5 years, all of Yates' novels have been reissued in the UK and the back covers are just lists of blurbs by various writers and critics lining up to praise him. I've bought the ones I needed, always thinking, somewhere deep down, that he was still mine, that I wouldn't let them take him away from me. Even when Blake Bailey's biography "A Tragic Honesty: the Life and Work of Richard Yates" came out in 2004, confirming that Yates was now something of a brand, as all successful writers are, I held onto this thought.

I know it doesn't make sense. Most of my favourite writers are universally acclaimed, massively successful, canonical authors. John Updike and F Scott Fitzgerald are not obscure in any way, and I love them both as much as if not more than I love Yates. I should be happy that Yates' genius is at last being recognised. And I think I am, on one level. But there it is anyway, the nagging resentment of it all, deep down in my gut.

What prompted all this was Richard Ford (yes, him again) and his introduction to a James Salter short story in last weekend's Guardian Review. Salter is another "writers' writer", and I've always maintained some obscure mental association between him and Yates. I found him by picking up a copy of "A Sport And a Pastime" one day in that same Dublin Waterstones from which I had ordered "Revolutionary Road". It was a very different experience, but similarly intense. Salter's writing is extraorinary - sentence by sentence he dazzles the reader with a tautly expressive poetry of feeling and description. Every word is perfectly weighted, every sentence precisely tooled in its effect, the cumulative experience strangely luminous and moving, yet also terse and sparse. Reading him, I wanted to write like him, a feeling only a few select authors bring about in me. He was easier to get into than Yates had been, mainly because he was still alive and still writing. After "A Sport And a Pastime" I moved on through the rest of his work, beginning with "The Hunters", his superb novel of fighter pilots in the Korean War. Then his autobiography, "Burning The Days" was released in 1997, and it told me that he had been a fighter pilot during that War, and also that he was a screenwriter and poet. But it told me all this in beautiful dreamlike little fragments, impressions of moments and moods, the Salter way. I've read all of his books since then except "the Arm of the Flesh" (which was available online from between £40 and £150 last time I checked), but he was so dissatisfied withit that he rewrote it as "Cassada" and so I feel alright about it eluding me.

He is an absolutely beautiful writer. "Light Years", his tale of the slow death of a marriage, is a miraculously lovely book, one of my favourites, and has just been reissued, alongside "The Hunters", as a Penguin Modern Classic. But Salter's best writing, generally, is all about flying. His vivid descriptions of soaring in the blue above the earth transform a subject from one in which I have little or no interest into a primal pursuit and source of fascination.

Though always critically acclaimed, Salter has never enjoyed as much success as even Yates did in his lifetime. No National Book Award nomination for him. Only one of his books has ever exceeded 10,000 sales on its first publication, that being "Solo Faces" in 1979. Its increased commerciality may be the result of the facts of its comissioning : Salter was hired by Robert Redford to write a screenplay about rock-climbing. When Redford disliked the result, Salter reworked it into a novel.

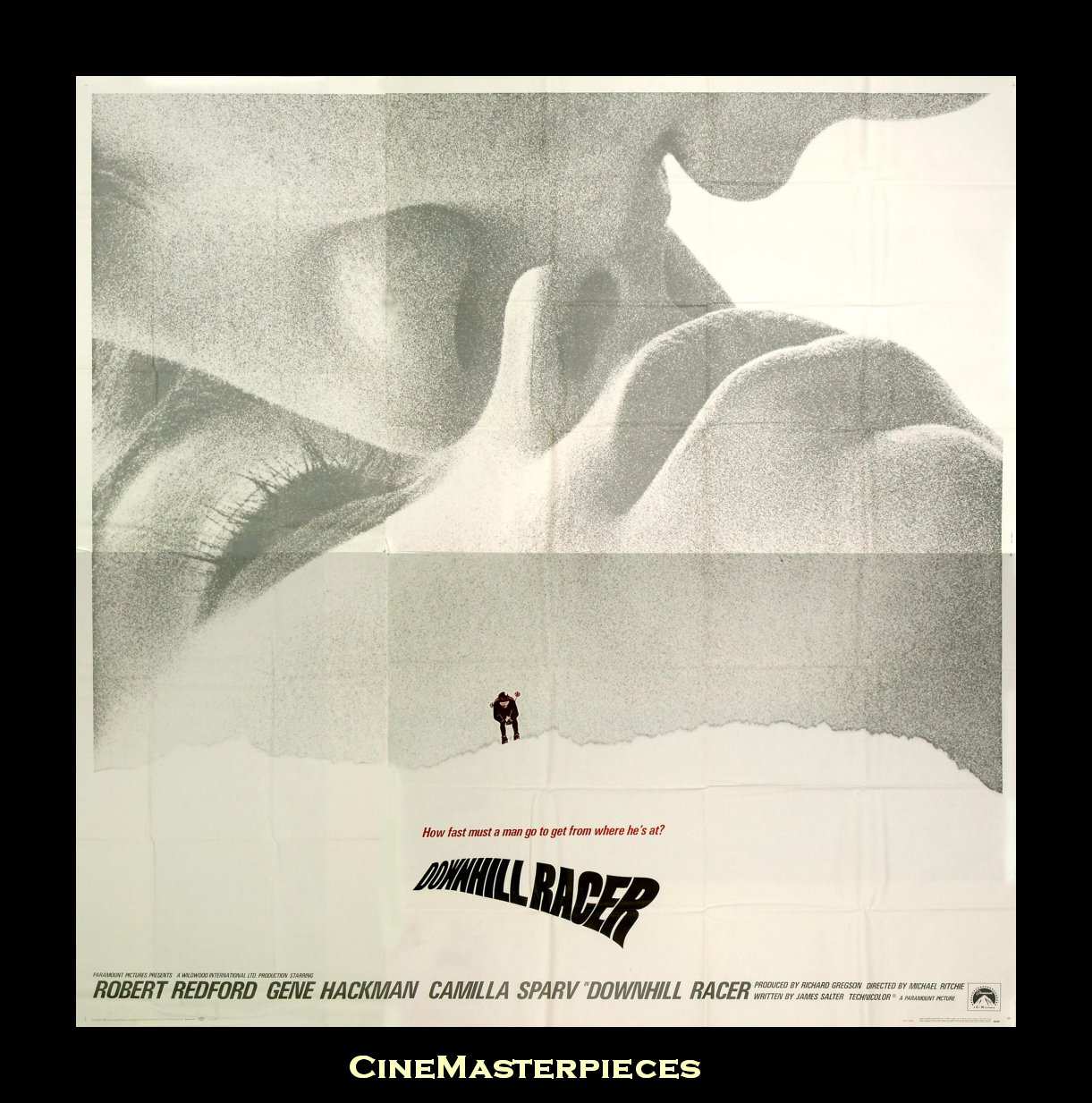

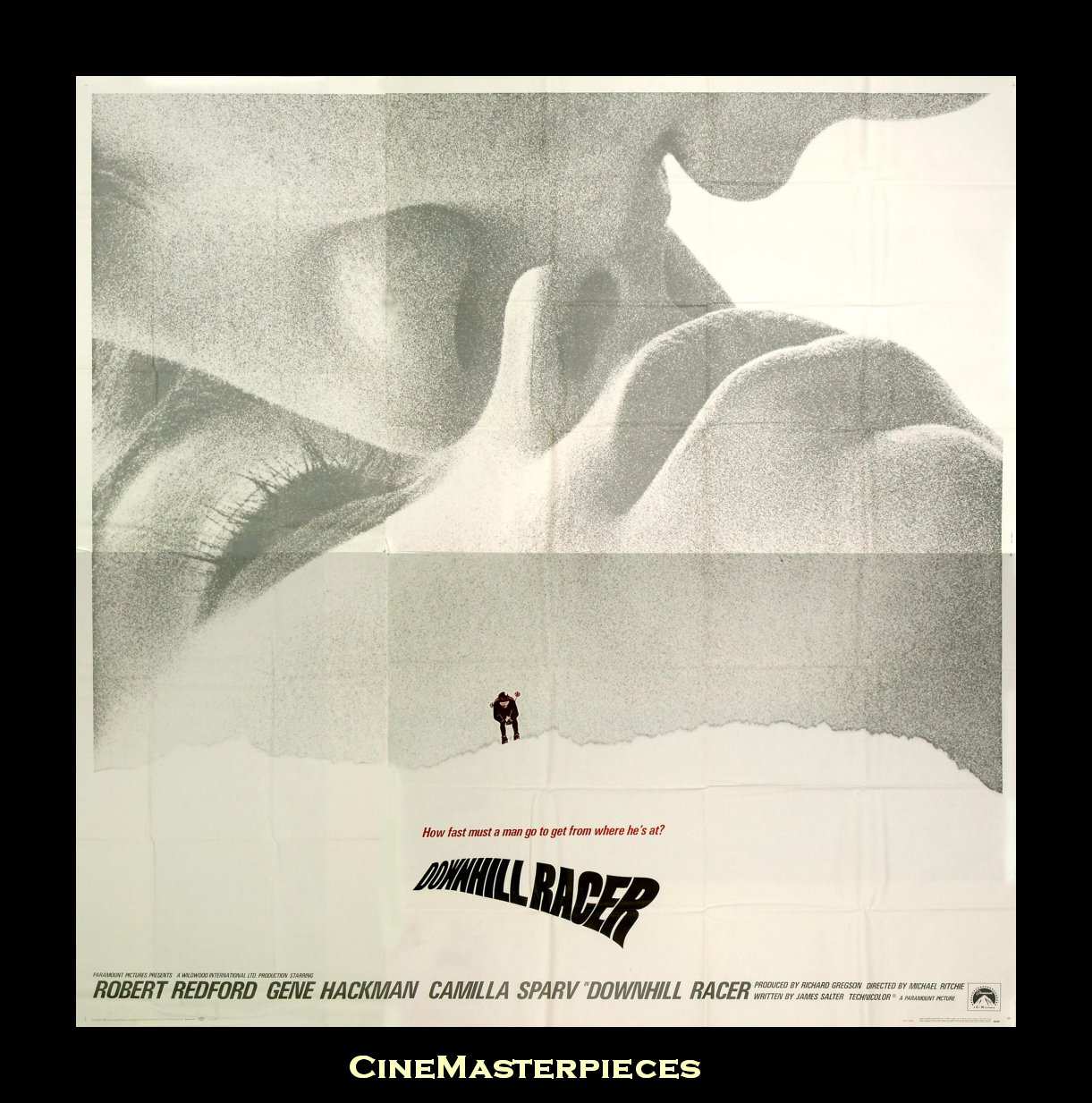

Unsurprisingly, that novel bears some similarity to Salter's work on the screenplay for "Downhill Racer", Michael Ritchie's 1969 character study of an Olympic Skier starring...Robert Redford. It features one of Redford's best performances, mainly because his character is far from sympathetic. Instead he is complex, selfish, unknowable, somehow only himself when skiing, and this suits the callowness of Redford's bland beauty and the easy charisma of his screen presence. But "Solo Faces" was written almost a decade later, and by then Redford was a much bigger star. He didn't play ambiguous characters anymore, and Salter probably can't bring himself to write anything else. Redford's loss was the reading publics gain.

Salter is still writing and still publishing. Last year, a new volume of short stories, "Last Night" and a collection of his travel writing, "There and Then" were both released. The feeling remains that, like Yates, his true worth and status in American literature will only be revealed after his death. Ford's acknowledgement in the Guardian probably won't change that, much as it makes me paranoid. And anyway, there are still writers the Zeitgesit hasn't spotted yet, maybe even a few it never will. Writers like Walter Tevis, author of the novels "The Hustler" and "The Man Who Fell to Earth", both of which became classic films, and of one of the greatest sci-fi novels I've ever read, "Mockingbird". Each of these books is heartbreaking in its own way, each written in Tevis' simple, defiantly unliterary prose, each profoundly readable in a way so many far more successful writers are not. Or like Jim Harrison, best-known as the writer of novellas upon which "Legends of the Fall" and "Revenge" were based, but done a disservice by both films, neither of which comes close to capturing the muscular epic feel of his best work, and how full it is of truth and painful humanity. It is instructive to note how often cinematic adaptations of novels are the driving force in bringing an author to the attention of the literary mainstream, and shows how powerful Hollywood really is in popular culture. If a book is turned into a film, even if the film is terrible, more people will become aware of the book, and some of them will want to read it.

Some other writers I love dance around the edge of the mainstream, best known for the books they have had turned into movies. James Jones was one of America's most popular literary novelists in the 1950s and early 60s. But hes one of those middlebrow writers, alongside the likes of John O'Hara and Irwin Shaw, who have faded, no longer fashionable, not as immediately distinctive as flashier peers like Pynchon and Bellow. He is now remembered chiefly because of the film versions of the first two volumes of his second world War trilogy, "From Here To Eternity" and "The Thin Red Line". The latter is one of the greatest novels of men in combat ever written, easily the equal of "The Naked and the Dead" or "All Quiet On the Western Front", though nowhere near as celebrated. Denis Johnson is one of the most versatile and talented American writers working today, turning his hand to novels, plays, poetry and journalism at various points in his career. His incredible series of sketches, vignettes and short stories about the life of a junkie and his friends, "Jesus Son", was turned into a movie by Alison Maclean in 1999. None of his other work, though just as worthy, has ever received anywhere near as much attention. Daniel Woodrell, whose writing has matured from backwoods noir to a sort of blue collar dirty realism without ever losing its baroque edge and unique sense of humour, is best-known for the film of his riveting Civil war novel, "Woe to Live On." Only Ang Lee renamed it, blandly, as "Ride With The Devil", when he adapted it in 1999. His adaptation, while interesting, doesn't capture the guttural squalor and violence of the novel, its messy intimacy. You get the feeling that Ang Lee would find it almost distasteful. Woodrell must curse his luck that Lee's film of his book was a massive flop, while his version of another Western-themed book, "Brokeback Mountain", became something of a phenomenon. But it makes me sort of happy, of course. His books get reviewed in the broadsheets books pages, but nobody I know reads him.

Then there are writers I feel confident will never really break through into the mainstream. They're just too perverse, or too unlucky. Geoff Dyer won't settle down and allow the public or the literary media to pigeonhole him. He writes novels, brilliantly (see "Paris, Trance" or "The Colour of Memory" for evidence), but then he writes books on photography ("The Ongoing Moment"), quasi-travel books ("Yoga For People Who Can't be Bothered to do It"), a book on his inability to write a book about D.H. Lawrence ("Out of Sheer Rage"), a book on John Berger ("Ways of Seeing") and a collection of his reviews and journalism ("Anglo-English Attitudes"). He'll never follow the sensible, one-novel-every-year-or-two years career path, meaning he'll probably never really gain mainstream success. George Pelecanos, an American crime novelist, is constantly being lauded as the next big thing, the Crime Writer's Crime Writer, a writer on the Wire, the best commentator on life in America's inner-cites writing today, and yet he has never actually really made it up to that top rank of Crime novelists. In terms of talent, he may well be the best working today, in company with James Ellroy. He is certainly better than the likes of Walter Moseley, latter-day Elmore Leonard and Michael Connelly, but his sales are a fraction of theirs. There are a couple of adaptations of his books in the works, though, which may change everything. But I don't know. For Pelecanos, it just doesn't look like it'll ever happen.

But then I'm sure fans of Jim Thompson thought like this at one point. Back before so many of his books had been turned into films, when they felt like only they understood him, like he was theirs. Before he became a brand, almost a cliche. I'm sure fans of Philip K Dick felt like this, too, at one time. And then the Zeitgeist came looking for food, and the mainstream came calling...

I hate that. I've had bands, of course. Back when I was younger and into slightly fashionable music, I suppose. I saw The Strokes on their first UK tour, in Dublin, when they had only released one single. But they already had a massive buzz around them and every hipster in the city was at that gig. A few months later, the album came out and they were huge. Mercury Rev prior to Deserters Songs. Wilco before Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. Elliott Smith. None of those acts are exactly U2, I know, but they all became a lot more successful at a certain point long after I had gotten to them, and its relative. I knew guys in school who were massive Nirvana fans from Bleach onwards, way before Nevermind came out. Imagine how they felt when that band, "their" band, the band that at one point almost nobody they talked to would have heard of, when that band became the biggest band in the world? I know it used to annoy me, stimulating some elitist nerve I carry around inside. It never feels the same afterwards, when the world has discovered something you love in an intensely private and personal way. The internet has changed so many things about the way we think about and consume music, and this is one of them. Nothing is obscure anymore. If you're interested in a band, they're out there, just a few keytaps away. Elitism is irrelevant. The internet doesn't care.

Instead, nowadays it happens to me mainly with writers. I'll give you an example: Richard Yates. I first heard of Richard Yates on the dedication to Richard Ford's collection of novellas, "Women With Men" in 1997. Ford, one of my favourite writers, thanks Yates. If it was good enough for Ford, it was good enough for me, and so I set off in search of Yates. Back then I didn't have a computer, I hadn't really used the net much, and so Amazon wasn't an option. So I had to go to regular bookshops in a fruitless quest. No Yates anywhere. I asked in Waterstones and there were no Yates books in print in Britain or Ireland. There was one available on import from America, but it would take around a month to arrive. I ordered it and a week or so later found a copy of Yates' "Young Hearts Crying" in a Dublin secondhand bookshop. That, perhaps Yates' worst novel, was the first thing I ever read by him. And it blew me away. I call it his worst novel, but it is only by comparison to the high standard of the rest of his work that it seems lesser. The simplicity of the writing, his fine storytelling, his observational skills and understanding of people, the sense of pessimism and loss in every page seemed incredibly fresh and vital to me. I had a new writer to love and read, always an exciting moment for a reader.

The book I had ordered from Waterstones turned out to be "Revolutionary Road", probably Yates' best and most famous work. Its also one of the bleakest novels I've ever read, but don't let that put you off. It was nominated for the National Book Award in 1962 alongside Joseph Heller's "Catch-22" and Walker Percy's amazing "The Moviegoer", in what constitutes an incredibly strong field of lasting quality. It follows the decline of the marriage of Frank and April Wheeler in the sterile suburbia of 1950s America with an acuity of vision not many writers can match. It is beautifully written in Yates' plain, understated prose, but the characterisation and deftly drawn relationships make it as gripping as any thriller. The bleakness of Yates' sensibility was obvious from reading just two of his books, but seemed essential to the quality of his work, somehow. He saw how the world was, and he recorded it precisely. I loved it, of course. It seemed impossible that a writer as brilliant as Yates evidently was could be so little-known. Why was he not acknowledged as one of the greats of 20th Century American literature? How had such an artist slipped through the net? Well, the net was slowly closing around Yates, though I didn't know it yet.

Back then, I was temporarily stymied in my quest for more Yates by the unavailability of anymore Yates. Once I gained Internet access I dicovered that some of his other books, though long out-of-print, were available secondhand online. I bought The Good School this way. I also found an article about him, written by Stewart O'Nan, another more-neglected-than-he-deserves American novelist, which was a good combination of brief biography and literary criticism. It descibed Yates as a "writers' writer". I liked that. Then his work started to dribble out in new editions. "Revolutionary Road" was first, with an introduction by Ford. It received brilliant reviews in the UK press. I felt the sting of that. Then a Collected volume of his Complete Short Stories. Which I bought, glad it was available to me but a little resentful, too. Over the last 5 years, all of Yates' novels have been reissued in the UK and the back covers are just lists of blurbs by various writers and critics lining up to praise him. I've bought the ones I needed, always thinking, somewhere deep down, that he was still mine, that I wouldn't let them take him away from me. Even when Blake Bailey's biography "A Tragic Honesty: the Life and Work of Richard Yates" came out in 2004, confirming that Yates was now something of a brand, as all successful writers are, I held onto this thought.

I know it doesn't make sense. Most of my favourite writers are universally acclaimed, massively successful, canonical authors. John Updike and F Scott Fitzgerald are not obscure in any way, and I love them both as much as if not more than I love Yates. I should be happy that Yates' genius is at last being recognised. And I think I am, on one level. But there it is anyway, the nagging resentment of it all, deep down in my gut.

What prompted all this was Richard Ford (yes, him again) and his introduction to a James Salter short story in last weekend's Guardian Review. Salter is another "writers' writer", and I've always maintained some obscure mental association between him and Yates. I found him by picking up a copy of "A Sport And a Pastime" one day in that same Dublin Waterstones from which I had ordered "Revolutionary Road". It was a very different experience, but similarly intense. Salter's writing is extraorinary - sentence by sentence he dazzles the reader with a tautly expressive poetry of feeling and description. Every word is perfectly weighted, every sentence precisely tooled in its effect, the cumulative experience strangely luminous and moving, yet also terse and sparse. Reading him, I wanted to write like him, a feeling only a few select authors bring about in me. He was easier to get into than Yates had been, mainly because he was still alive and still writing. After "A Sport And a Pastime" I moved on through the rest of his work, beginning with "The Hunters", his superb novel of fighter pilots in the Korean War. Then his autobiography, "Burning The Days" was released in 1997, and it told me that he had been a fighter pilot during that War, and also that he was a screenwriter and poet. But it told me all this in beautiful dreamlike little fragments, impressions of moments and moods, the Salter way. I've read all of his books since then except "the Arm of the Flesh" (which was available online from between £40 and £150 last time I checked), but he was so dissatisfied withit that he rewrote it as "Cassada" and so I feel alright about it eluding me.

He is an absolutely beautiful writer. "Light Years", his tale of the slow death of a marriage, is a miraculously lovely book, one of my favourites, and has just been reissued, alongside "The Hunters", as a Penguin Modern Classic. But Salter's best writing, generally, is all about flying. His vivid descriptions of soaring in the blue above the earth transform a subject from one in which I have little or no interest into a primal pursuit and source of fascination.

Though always critically acclaimed, Salter has never enjoyed as much success as even Yates did in his lifetime. No National Book Award nomination for him. Only one of his books has ever exceeded 10,000 sales on its first publication, that being "Solo Faces" in 1979. Its increased commerciality may be the result of the facts of its comissioning : Salter was hired by Robert Redford to write a screenplay about rock-climbing. When Redford disliked the result, Salter reworked it into a novel.

Unsurprisingly, that novel bears some similarity to Salter's work on the screenplay for "Downhill Racer", Michael Ritchie's 1969 character study of an Olympic Skier starring...Robert Redford. It features one of Redford's best performances, mainly because his character is far from sympathetic. Instead he is complex, selfish, unknowable, somehow only himself when skiing, and this suits the callowness of Redford's bland beauty and the easy charisma of his screen presence. But "Solo Faces" was written almost a decade later, and by then Redford was a much bigger star. He didn't play ambiguous characters anymore, and Salter probably can't bring himself to write anything else. Redford's loss was the reading publics gain.

Salter is still writing and still publishing. Last year, a new volume of short stories, "Last Night" and a collection of his travel writing, "There and Then" were both released. The feeling remains that, like Yates, his true worth and status in American literature will only be revealed after his death. Ford's acknowledgement in the Guardian probably won't change that, much as it makes me paranoid. And anyway, there are still writers the Zeitgesit hasn't spotted yet, maybe even a few it never will. Writers like Walter Tevis, author of the novels "The Hustler" and "The Man Who Fell to Earth", both of which became classic films, and of one of the greatest sci-fi novels I've ever read, "Mockingbird". Each of these books is heartbreaking in its own way, each written in Tevis' simple, defiantly unliterary prose, each profoundly readable in a way so many far more successful writers are not. Or like Jim Harrison, best-known as the writer of novellas upon which "Legends of the Fall" and "Revenge" were based, but done a disservice by both films, neither of which comes close to capturing the muscular epic feel of his best work, and how full it is of truth and painful humanity. It is instructive to note how often cinematic adaptations of novels are the driving force in bringing an author to the attention of the literary mainstream, and shows how powerful Hollywood really is in popular culture. If a book is turned into a film, even if the film is terrible, more people will become aware of the book, and some of them will want to read it.

Some other writers I love dance around the edge of the mainstream, best known for the books they have had turned into movies. James Jones was one of America's most popular literary novelists in the 1950s and early 60s. But hes one of those middlebrow writers, alongside the likes of John O'Hara and Irwin Shaw, who have faded, no longer fashionable, not as immediately distinctive as flashier peers like Pynchon and Bellow. He is now remembered chiefly because of the film versions of the first two volumes of his second world War trilogy, "From Here To Eternity" and "The Thin Red Line". The latter is one of the greatest novels of men in combat ever written, easily the equal of "The Naked and the Dead" or "All Quiet On the Western Front", though nowhere near as celebrated. Denis Johnson is one of the most versatile and talented American writers working today, turning his hand to novels, plays, poetry and journalism at various points in his career. His incredible series of sketches, vignettes and short stories about the life of a junkie and his friends, "Jesus Son", was turned into a movie by Alison Maclean in 1999. None of his other work, though just as worthy, has ever received anywhere near as much attention. Daniel Woodrell, whose writing has matured from backwoods noir to a sort of blue collar dirty realism without ever losing its baroque edge and unique sense of humour, is best-known for the film of his riveting Civil war novel, "Woe to Live On." Only Ang Lee renamed it, blandly, as "Ride With The Devil", when he adapted it in 1999. His adaptation, while interesting, doesn't capture the guttural squalor and violence of the novel, its messy intimacy. You get the feeling that Ang Lee would find it almost distasteful. Woodrell must curse his luck that Lee's film of his book was a massive flop, while his version of another Western-themed book, "Brokeback Mountain", became something of a phenomenon. But it makes me sort of happy, of course. His books get reviewed in the broadsheets books pages, but nobody I know reads him.

Then there are writers I feel confident will never really break through into the mainstream. They're just too perverse, or too unlucky. Geoff Dyer won't settle down and allow the public or the literary media to pigeonhole him. He writes novels, brilliantly (see "Paris, Trance" or "The Colour of Memory" for evidence), but then he writes books on photography ("The Ongoing Moment"), quasi-travel books ("Yoga For People Who Can't be Bothered to do It"), a book on his inability to write a book about D.H. Lawrence ("Out of Sheer Rage"), a book on John Berger ("Ways of Seeing") and a collection of his reviews and journalism ("Anglo-English Attitudes"). He'll never follow the sensible, one-novel-every-year-or-two years career path, meaning he'll probably never really gain mainstream success. George Pelecanos, an American crime novelist, is constantly being lauded as the next big thing, the Crime Writer's Crime Writer, a writer on the Wire, the best commentator on life in America's inner-cites writing today, and yet he has never actually really made it up to that top rank of Crime novelists. In terms of talent, he may well be the best working today, in company with James Ellroy. He is certainly better than the likes of Walter Moseley, latter-day Elmore Leonard and Michael Connelly, but his sales are a fraction of theirs. There are a couple of adaptations of his books in the works, though, which may change everything. But I don't know. For Pelecanos, it just doesn't look like it'll ever happen.

But then I'm sure fans of Jim Thompson thought like this at one point. Back before so many of his books had been turned into films, when they felt like only they understood him, like he was theirs. Before he became a brand, almost a cliche. I'm sure fans of Philip K Dick felt like this, too, at one time. And then the Zeitgeist came looking for food, and the mainstream came calling...

Labels: books

8 Comments:

This is, more or less the French national identity isn't it?

"We liked him when you thought he was a bum. We've liked him for years. What do you people know? We published magazines dedicated to his work, and yet, he was out of print in your stinking country when he died. Fools! Putain!"

I don't mean that disrespectfully.

The french people I know like Star Trek and France. That's my only frame of reference. I'm kinda under the impression they like cycling also.

The only writers I get into are generally recommended to me, so as far as I'm aware they're exceedingly popular before I have a clue as to who they are.

Pretty much anyone who tells me they love Hunter S Thompson gives me some comfort though, as none of them have read anything apart from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. I get to talk about On The Campaign Trail '72 and Better than Sex and I feel clever.

Futureheads kinda felt like a 'my band' for a while, but I doubt they ever were really. I barely listen to them now...if at all.

I think it's just some kind of hipster ego thing (in my case anyway), I just want to have some kind of trendy edge. I'm desperately trying to keep down with the kids. It's futile.

So some people you like actually got to make a living out of doing the stuff you like them for and could afford to quit their bummy jobs. This is ice cream not black dog.

I know its good, of course, it doesn't make any sense. I recommend stuff to people endlessly. I bully people to buy the Wire on DVD, then I feel a bit miffed when the Guide in the Guardian has it on its cover. And I know that I might even be contributing to it, in my teeny little way, with this blog. But its human nature, I think.

Plus it was the best way I could think of to group together some writers I wanted to talk about...

Black dog? Ice cream? those terms have no meaning here.

'course now it's happening with phrases. Guardian prints an article about the popularity of 'Meh'? So now those who weren't fully aware of its uses can steal it for themselves?

Bah.

Meh, eh? Kind of like bling. Imagine how 'people of colour' feel, with whole tracts of culture 'discovered' by the middle class media in chunky bursts.

Language, art and music all appropriated by the man.

Or something.

I had this with combats before All Saints started wearing them and they turned into 'cargo pants'. I bought some from Reading for a fiver, and not at the festiva, at the city - my first girlfriend was from there when I was 16. I gained an intimate knowledge of Victoria coach station.

I was into Marilyn Manson, Fear Factory and Korn before Kerrang took note, and they all slid downhill. I was into Tool from way back.

I got into the new Asian film boom before Tartan did.

Chris Morris I joined on the up but before the peak, Radio 1 show but after GLR.

I don't have a point.

Your point, my friend, is that you are cool. Which is my subtext, I suppose. Look at me, my taste is cool. I like cool stuff. All you people who like it after me aren't as cool as me and your lack of coolness while liking something that I like still doesn't detract from my own coolness because I have self-awareness. Cool?

Isn't cool a strange word for denoting quality or the aura of fashionability? I rarely question it, because its been acceptable slang for most of my life, but its a strange usage, I think.

Come to think of it, is it even slang anymore?

Meh.

Blame Miles Davis.

Post a Comment

<< Home